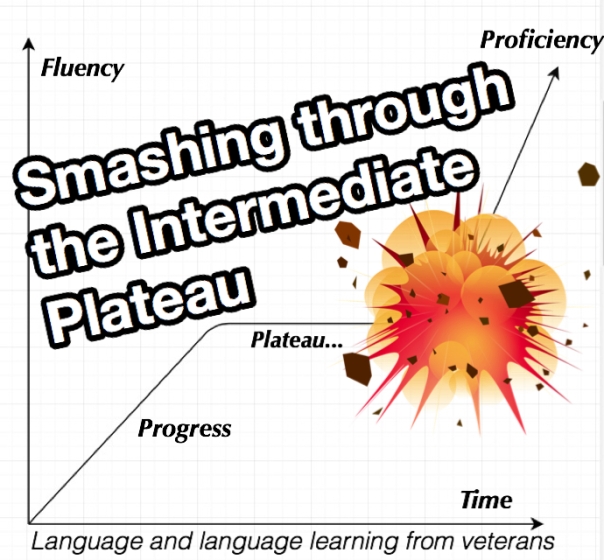

There comes a time in the life cycle of every language learning experience where the student is hit by a brick wall. I have experienced this myself while learning, or trying to learn Irish, French, German, Spanish, Latin and Italian. I have seen other learners go through it as both a teacher and a friend. The usual course of events is this: the learner starts out by picking up a great deal of high frequency vocabulary, which gives them an extremely profitable return on their investment. These high frequency words are often heard and seen in reading and listening input and quickly become acquired, making the learner feel like rapid progress is being made. This happy state of affairs remains as the learner progresses through A1 and A2 levels on the CEFR and continues into intermediate stages. With each hour spent acquiring, vocabulary texts become progressively more penetrable, thus positively re-enforcing learner behaviour.

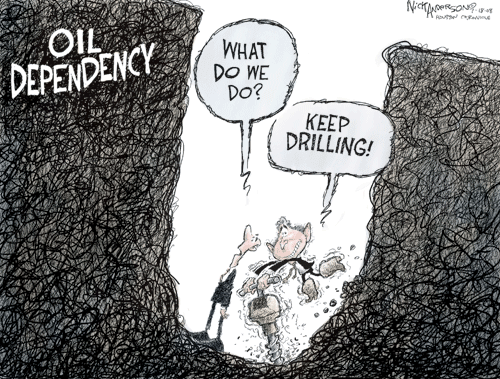

This encouraging state of affairs continues unabated right up until the quagmire that is the B1-B2 crossover point. Think of it as a dark foreboding forest where only the most valiant warriors emerge. The honeymoon phase is over. This phase creates the false impression that languages are easy to learn. Well, they are at first, that is until the learner runs out of high frequency vocabulary to learn. Then, the tables are turned, high frequency vocabulary runs out and learners became faced with the bleak prospect of learning a word which they mightn’t come across again for weeks if not months. This can happen even in a situation where the quantity of input is extremely high, such as can be found in a full immersion environment. This land of no return is well know by language learners and it’s the last stop on the line for many of them. The trains stops and they get off far out in the suburbs.

Polyglots can also experience this stage, having said that it is more rare once you’ve mastered your first second language. I will attempt to address why this is the case later.

Firstly, I want to point out that this stage, sometimes termed the intermediate plateau, is not necessarily a bad thing. This level of proficiency serves many learners well. Let’s imagine a Korean business woman in the IT industry on a trip to her company’s supplier in Vietnam, who happen to make parts for her company’s mobile phones, to oversee new standards of production. Her hosts are equally proficient in the language, and together the happy group negotiate meaning during the visit. Error counts are high- but who cares? There is no teacher around to write down their mistakes and communication, while imperfect, is mostly successful. It’s all about getting the message across and if she doesn’t happen to know how to use the present perfect tense very well-well who cares? If she doesn’t happen to have the word for a particular noun- let’s say ‘a blanket’ in the hotel that she’s staying in- well, she can just show the receptionist a picture on her mobile phone. She could go on holidays the following year to France and have a very similar experience. In short, meaning is negotiated, thrashed out if you like, between two or more willing parties.

The majority of English as a second language speakers around the world are on the plateau and are happy there. They learned the language to get by, not to understand the intricacies of assonance in Grey’s Elegy, nor watch The Godfather Trilogy without subtitles and certainly not to give a talk at a TEDX conference or publish articles in peer-reviewed journals. Their ambitions are much more modest and mediocre works just fine for them in their world thank you very much.

Sounds great, right? And remember practice makes perfect, doesn’t it? So these intermediate plateau learners (IPLs) will inevitably get better as they continue dealing with the language, right? No, that’s where we are sometimes mistaken. This isn’t my line but I wish it was, practice doesn’t make perfect but perfect practice does. If you want to progress to C1 and C2 and beyond, your learning behaviours need to change.

Before I discuss practising more perfectly, I want to quickly explore the other factor which creates the illusion that languages are easy to learn at lower levels. This is the unequal way we have divided up language learning courses into a series of levels. Be it the CEFR, IELTS bands or the old beginner to proficiency system, schools, course books and teachers do not make it clear to students that the time it takes to get from A1 to A2 is not the same as the time it takes to get from C1 to C2, not by a long shot. Think of A1-A2 as the Apollo mission to the moon and C1 to C2 as getting to Mars (and setting up a colony there). Similarly, getting from band 5 to 6 in IELTS can be done in 3 months while getting from 8 to 9 may take 3 years or 30.

Ok so language acquisition is more rapid at the beginning but once progress slows down, how can we make the time we devote to learning a language more worthwhile?

It’s not a revelation, or at least it doesn’t seem so at first, but it is. I mentioned polyglots before. They go through the intermediate plateau in their first second language as all other learners but they manage to find their way out of the forest. They master their L2. L3 is a much easier experience. The brain has been rewired to become highly attuned to acquiring. The difference between L2 and L3 for the typical polyglot is like the difference between getting a taxi from the airport to your hotel or standing in the rain waiting for a bus that’s late and trying to understand the bus maps that are in a foreign language. For the polyglot, it becomes an enjoyable experience to go from elementary to proficiency in your L3. L4 is almost done on autopilot and it gets even easier from there. Now don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying that learning a language, even your fourth is easy. On the contrary, it still takes a huge investment of time. However, what reduces is the frustration of performing learning behaviours that give little return on investment. Enjoyment increases. The pleasure of improving is felt much more often, at all proficiency levels, and there is very little of the frustration.

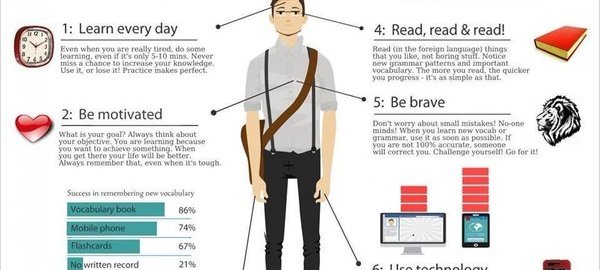

What do polyglots do then that’s different? Well, for one they tend to be extremely disciplined. Just like physical exercise, a little bit on a regular basis goes a long way. They stay relaxed and do not stress to much about their level or undergo anxiety during production. They’re constantly trying out what they know and taking feedback on board, always trying to do better next time. However, they can be happy to remain silent and simply soak up what’s going on around them. They look at grammar only on a need to know basic and don’t make the mistake of trying to learn the third conditional before they’ve even noticed it during input. They have modest goals, at least at first. These might be to have a enough Italian to order food in a restaurant or hold a conversation about football in German. They find input that’s comprehensible. And of course they keep motivated, which brings me to the key ingredient: avoiding boredom.

Boredom is the mortal enemy of acquisition. Polyglots have developed techniques for avoiding this boredom and its associated frustration on the intermediate plateau. One of the ways of achieving this is to change the learning source frequently. For example, if you’ve been doing French on Duolingo for a few months and have made a lot of progress but are getting a bit fed up with the routine of it all? Say you’ve read all the graded readers in your local library, you’ve got all of Axelle Red’s CDs and you’re sick of trying to read Camus’ L’étranger. Well, try another source- read BBC Afrique, watch TV5 and France 24 and listen to Europe 1. Download some podcasts. Find a TV programme from the Francophone world that you like, for example ‘Un Village Français’, have a look on YouTube for an interesting French language blogger- why not one from Cameroon? Find a language swap in your town. Find 10 of them. In short, change the channel and when you get bored: change again, stay on the same language but change the channel. Find a new French class, watch a documentary in French about a topic that you’re familiar with. Listen or watch to whatever you like so long as it’s in French and so long as you find it interesting. Watch things that you enjoy multiple times. That’ll make it more comprehensible with each listen. Acquisition is INEVITABLE once you stay relaxed, avoid boredom and keep that input comprehensible. Oh an get copious amounts of it: between 2 and 4 hours every day. C’est facile, non?

This is the fourth of the series of posts on the talks I attended at TESOL Italy 2015. You can read the previous ones here:

This is the fourth of the series of posts on the talks I attended at TESOL Italy 2015. You can read the previous ones here: