[This article was originally published as What happened to drilling? in the BELTA Bulletin in October 2014. It’s available on-line for BELTA members here. It’s reprinted here with the permission of the editor.]

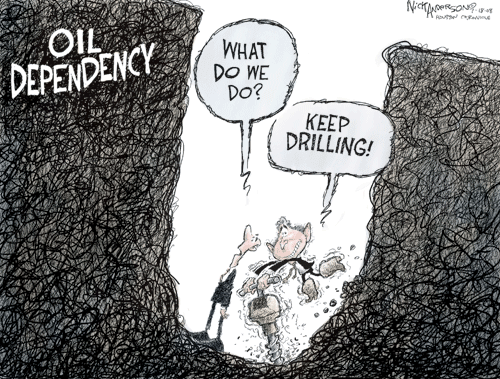

As communicative language teachers we are told that drilling is bad. We’re told it is pointless, uncommunicative and deprived of any meaning. It also makes our classes teacher–centred.

Before you jump on the bandwagon and continue the rant, I’d like you to pause for a moment and ask yourself whether drilling really has to be so horribly boring and uncommunicative as we are repeatedly told. I hope to show you with this article that, no – drilling doesn’t have to be boring. It can actually be fun, meaningful, effective and rewarding for the students.

In this article I’m going to first look at eight common criticisms of drilling and controlled oral practice (COP) and show why they are not all together accurate. Then I’ll describe a couple of COP activities which you can use in class, and offer some final tips on using COP.

Let’s then look at the criticisms.

- Criticism: Too much emphasis put on accuracy, hindering the development of real communication skills. Rebuttal: It is true that these exercises focus on accuracy. CLT does not. And this is why a little bit of COP can do your students a lot of good. By no means should COP become the main focus of all your lessons. It’s only part of the diet, like broccoli. And even though we might not like the taste, we still eat it every now and then, because we know it’s good for us. The same rule applies to COP.

- Criticism: Only useful when practising language students have just encountered. Rebuttal: Usually COP is seen as a prelude to the real icing on the cake, that is, the free speaking activity. But why not use it as a quick revision to address fossilised errors, or give students quick extra practice in something they are struggling with?

- Criticism: COP is only applicable and valid when teaching lower levels. Rebuttal: Why should that be? COP can and should be used at any level. It helps students automatise the language they might already know but still struggle to use confidently and naturally, or eradicate fossilised errors.

- Criticism: COP does not promote learner autonomy and is teacher–centred. Rebuttal: That would be true if your class were to consist entirely of COP. If done judiciously, it is actually empowering since students will get more comfortable with the language, and are more likely to use it later on in more communicative activities. And it does not need to be teacher–centred. Put them in pairs. Put one student in charge of the drill. There are a number of options which allow you to disappear.

- Criticism: Usually only word or sentence–based, decontextualised and very restrictive. Rebuttal: Whenever possible, use real–life situations. Set the context and make it meaningful. Try to implement natural features of the spoken discourse into your drill. Use drills which allow for more than one answer, and which are more flexible.

- Criticism: It goes against some styles of teaching, especially the role of the teacher as a facilitator. Rebuttal: Give it a go. Once you and your students get comfortable with it, COP can become an important part of your facilitative approach. Just don’t overdo it. Too much of anything is never good. But if done correctly, COP can be really enjoyable for the students. It can also nicely change the focus and pace of the class.

- Criticism: Being able to repeat in a parrot like fashion does not mean the student will remember or be able to use the language in real conversation. Rebuttal: That might be true. But then if they don’t repeat the language a few times in a safe and controlled environment, will they be more or less likely to use it in a real conversation? Probably less. Plus, what they are trying to memorise and automatise, are not the examples they are drilling, but the language patterns embedded in them. COP can also help with avoidance.

- Criticism: The course book writers ignore it, and so should I! Rebuttal: Since the advent of CLT, drilling has been heavily put down, and course book writers responded by ignoring COP in their materials. It’s like switching from only eating meat to being a vegan.

Having dealt with some of the most common criticisms, let’s look at examples of COP.

Substitution Drills:

This is probably the COP I’ve used most often myself, as it’s readily applicable for almost any language point. The basic idea is that the learners repeat the modelled grammar using the new information given, e.g. “I’ve been reading for two hours”.

T: midday

S: I’ve been reading since midday.

T: she

S: She’s been reading for two hours.

Make sure the examples lead to meaningful and probable sentences. Once you and your students get comfortable with this drill, consider some of the below variations, which aim to increase the cognitive difficulty and make the COP more natural and meaningful.

Multiple Substitution Drills:

Instead of substituting one item, students substitute two. So with the example from above:

T: he/drinking

S: He’s been drinking since midday.

Progressive Drills:

The difference between this one and the classic substitution drill is that you don’t come back to the original sentence, but continue from the last. If you do it as a whole class, it causes other students to listen carefully to what the previous student has said as they’ll have to pick up from there.

T: play football

S1: He’s been playing football since midday.

T: two hours

S2: He’s been playing football for two hours.

Open ended Drills:

Students repeat the modelled language, or finish a sentence, making it logical or true for themselves. The idea is they have to manipulate not only the grammar, but more importantly fill in the content in a very short time, which cognitively is of course much more challenging then a classic substitution drill. At the same time, it is arguably more natural. For example, to practice “in order to/so that” for purpose:

T: Why do birds have wings?

S: In order to fly./So that they can fly (or anything else that makes sense)

True/False drills:

Students manipulate the content of the sentence to make it true or false for them. They are more challenging cognitively and require the learners to process the language at a slightly deeper level. They are also more meaningful than classic substitution drills. For example, to practice “used to”

T: play football

S1: I used to play football as a child

S2 I didn’t use to play football as a child.

Mumble/Silent drills:

The teacher models the TL and the students repeat it quietly. It’s less intimidating then doing it out loud, and the students can be told to repeat the same phrase a few times under their breath, which gives them more practice and increases their confidence (I also assign it to my students as a ongoing HW, i.e. speak to yourself quietly or in your mind and repeat the language you have problems with.

Back–chaining:

A sentence is built from the end by adding short (between eight and ten syllables), natural chunks of language. Each chunk is modelled by the teacher and repeated by the students.

- the test

- for the test

- for the test

- should have

- should have studied

- I should have studied

- I should have studied for the test.

As Chris Ozog suggests in his article (see references below), we should focus on natural chunks of language, i.e. it would have been odd to drill have studied as a chunk. He also points out that back-chaining “also serves to promote noticing of features of connected speech” and “may help the students recognise fluently delivered English better”.

Jazz Chants:

They involve repetition of short, multi-word phrases at a consistent rhythm. They were popularised by Carolyn Graham, and here you can see video of her demonstrating how to create your own jazz chant.

To sum up, any good COP should fulfil one or all of the below aims:

- to establish new habits and minimise or get rid of the bad ones, some of which might be deeply ingrained (e.g. fossilisation, avoidance)

- boost learners confidence with language by practising it at reasonably natural speed

- to increase spontaneity, i.e. to facilitate making the quantum leap from having to think about it very hard, to simply saying it correctly without thinking (Wilson, M.)

You might consider making these aims clear to your class. Students often want to know why they are doing what they are doing. And if they understand that the purpose of the activity is to improve their speaking, they are much more likely to give it a go, despite some initial reluctance.

Read up and continue drilling:

- Clark, M. Yes, Drill Sergeant! http://www.bridgetefl.com/yes-drill-sergeant-how-to-use-efl-practice-drills/

- Kerr, P. Minimal Resources: Drilling. http://www.onestopenglish.com/support/minimal-resources/vocabulary/minimal-resources-drilling/146558.article

- Ozog, Ch. Don’t drill it. Drill it! Drill it now! http://eltreflection.wordpress.com/2012/05/18/256/

- Pearson, J. 1998. Communicative drilling. http://www.matefl.org/_mgxroot/page_10672.html

- Renshaw, J. Using and expanding speaking drills. http://jasonrenshaw.typepad.com/jason_renshaws_web_log/2009/09/supplementary-speaking-activities-part-iii-using-and-expanding-speaking-drills.html

- Wilson, M. Say it better. Maximum speaking practice.

![Meu instantâneo 15 [3677412]](https://teflreflections.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/meu-instantc3a2neo-15-3677412.png?w=186&h=186) Paolo Torresan obtained his PhD in Linguistics and Romance Philology at Ca’ Foscari University, in Venice. He has carried out research at Complutense University, Autonoma University, in Madrid, and at Lancaster University. He has taught at Rio de Janeiro State University and Santa Monica College, Santa Monica, CA. He is Editor-in-chief for the following journals: Officina.it and Bollettino Itals. Among his books we mention: The Multiple Intelligence Theory and Language Teaching (Perugia 2010). He’s also studied improvisation at the

Paolo Torresan obtained his PhD in Linguistics and Romance Philology at Ca’ Foscari University, in Venice. He has carried out research at Complutense University, Autonoma University, in Madrid, and at Lancaster University. He has taught at Rio de Janeiro State University and Santa Monica College, Santa Monica, CA. He is Editor-in-chief for the following journals: Officina.it and Bollettino Itals. Among his books we mention: The Multiple Intelligence Theory and Language Teaching (Perugia 2010). He’s also studied improvisation at the