This is the fourth of the series of posts on the talks I attended at TESOL Italy 2015. You can read the previous ones here:

This is the fourth of the series of posts on the talks I attended at TESOL Italy 2015. You can read the previous ones here:

- ELF and TESOL: a change of subject? plenary by Henry Widdowson

- Learning to teach listening: students’ and teachers’ perceptions. by Chiara Bruzzano

- ‘How to join communicative pressure and cooperation in a speaking or writing activity’ by Paolo Torresan

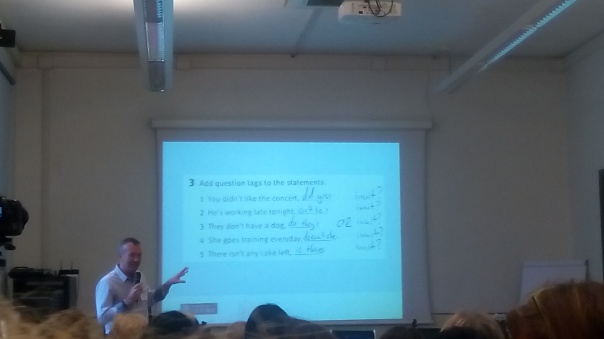

The session started with prompts for questions from which we had to formulate correct questions to ask our partner. Afterwards, we had to try to remember the information we heard, and check with our partner it was right by asking tag questions. This can be seen below:

But why bother with the complexities of the ‘correct’ question tags, if we can simply use ‘innit?’ in all cases. Or can we?

Of course, many would argue that ‘innit’ as a question tag is uneducated, uncultivated, vulgar and – worst of all – ungrammatical! But is it? Jon Hird’s talk aimed to question the prescriptive attitude to the language, and through vivid and hilarious examples of language (mis)use show that any language, especially one as extensively used as English, is a living thing which never stops evolving and changing.

However, attempts to dictate and prescribe what is ‘correct’ English are by no means new. Already a few hundred years ago Jonathan Swift was convinced that attempts must be made in order to ‘ascertain’ and ‘fix’ the English language forever. A very often used argument to support this is that otherwise the language will inevitably decay, and that ‘vulgar’ forms will become the norm, while the ‘cultivated’ and ‘correct’ ones will be forced into oblivion (you can read my post about what is ‘correct’ English here, and a listening lesson plan on a similar theme here).

Despite such claims, there is of course no evidence that this might have happened in the past or might occur at any time in the future. Interestingly, as far as English is concerned, there are only a few dozen grammar features that are considered non-standard. So in the next part of the talk, we look at some examples of non-standard English.

The first example is by Jagger: “Come off of it”.

The second one is now spreading very rapidly (as a grammar plague?), not just in English, but also in other languages (it’s definitely the case in Polish and Spanish, and a teacher sat next to me said that Swedish was one of the victims of this grammar ‘vulgarism’ too). So, many English speakers now use less both with countable and uncountable nouns. It has become so common that we hardly notice it any more, unless a grammar pundit points it out. This results in famous companies making grammar ‘mistakes’ in their ads. For example, British Airways might tell you that there are “less than 10 seats left”. If you’re thinking of grabbing a quick coffee, go for Starbucks, because they are a green company, and as they put it: “Less napkins. More plants. More planet”. Can’t argue with that.

Next comes the example of the infamous tag question we already saw at the very beginning, innit? The tag is so widespread, that it’s well bad, innit? It was wicked, innit? He’s not coming, innit? And so on. Just stop by and listen to how people speak. There’s no more room for the ‘correct’ question tags. They’re too cumbersome. Too long. Too varied. Innit?

Another example of non-standard English is teenspeak. One of the examples that entered ‘adultspeak’ and became quite widespread and popular a few years ago was chillax. What a brilliant word! I remember hearing it for the first time, and it was almost a revelation. Now you could chill and relax at the same time. And you had a word that described it! Well bad, innit? Unfortunately for the teens, as soon as they found out the word was spreading among adults, they had to drop it. It wasn’t wicked any more.

But if we had to choose a word in English that was by far the most widely spread and used more frequently, it would have to be ‘like’. Jon shows us a transcript of his teenage son speaking which very clearly illustrates that ‘like’ is everywhere now:

One more example Jon gives is LOL. First used on the Internet, it’s now started an exciting and adventurous linguistic life of its own. In short, it’s gone completely out of control. So now you can say: lol at you! Lols! That’s so lols!

I literally lolled when I saw these examples.

For some, this is a clear indication that language is going to the dogs. And if this decay is to be prevented and reversed strict measures need to be taken. For example, banning certain words from use:

One aspect of English that tends to drive some grammar pundits up the wall is the uncanny ability of the English language and its speakers to turn any word into a verb. Even LOL is now a verb. Anything can be a verb. As Humpty Dumpty put it, the only question is, who is to be the master. And verbing, as it’s sometimes called (yes, apparently ‘verb’ is a verb too), has been going on for centuries. According to Pinker, “It’s what makes English English”.

But of course, certain people don’t like the way in which this process ‘impacts’ the English language. For example, BBC went as far as banning the use of ‘impact’ as a verb. We can only see how this might ‘impact’ the English used by BBC reporters, but looking back at the history of English, ‘impact’ as a verb is there to stay.

There are many other more interesting examples of verbing words in English, though. For example, if you’re on Twitter, you can ‘favourite’ others’ tweets. No one questions that now you ‘google’ things. However, you might want to ‘wikipedia’ it too. And if you’re playing Angry Birds, well, you can angrybirds it up, yo!

So, did you have a good time conferencing? I certainly did. And Jon’s talk was well bad, innit?

PS The issue English teachers are faced with is whether any of the above uses of language should be taught in class. They’re incredibly widespread, and students – especially the ones studying in an English-speaking country, or watching a lot of TV and films in English – are bound to come across them sooner or later. Would you teach ‘innit’, ‘like’ or verbing to your students? Why (not)? Let me know what you think in the comments section.

![Meu instantâneo 15 [3677412]](https://teflreflections.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/meu-instantc3a2neo-15-3677412.png?w=186&h=186) Paolo Torresan obtained his PhD in Linguistics and Romance Philology at Ca’ Foscari University, in Venice. He has carried out research at Complutense University, Autonoma University, in Madrid, and at Lancaster University. He has taught at Rio de Janeiro State University and Santa Monica College, Santa Monica, CA. He is Editor-in-chief for the following journals: Officina.it and Bollettino Itals. Among his books we mention: The Multiple Intelligence Theory and Language Teaching (Perugia 2010). He’s also studied improvisation at the

Paolo Torresan obtained his PhD in Linguistics and Romance Philology at Ca’ Foscari University, in Venice. He has carried out research at Complutense University, Autonoma University, in Madrid, and at Lancaster University. He has taught at Rio de Janeiro State University and Santa Monica College, Santa Monica, CA. He is Editor-in-chief for the following journals: Officina.it and Bollettino Itals. Among his books we mention: The Multiple Intelligence Theory and Language Teaching (Perugia 2010). He’s also studied improvisation at the